Nooria, who was an English educator before the Taliban takeover, has been secluded from everything since the gathering held onto power

In an unexceptional white plastic pack, Ammar conveyed a grip of papers that are among his most valuable possessions at the present time.

It would've drawn in a lot of consideration for us to visit his home, so on his cruiser, he'd come to meet us at a safe area, terrified during the excursion that he could get looked at a Taliban designated spot and they could track down the papers.

The reports incorporated his agreement as an instructor with the British Council for quite some time, and other proof of his relationship with the UK, that he expectations will assist with getting him and his family to somewhere safe and secure. He fears for his life as a result of his work with the UK government.

"We showed the way of life of the United Kingdom and their qualities in Afghanistan. Notwithstanding the English language, we likewise showed about balance, variety and consideration. As indicated by their [Taliban] convictions, it is out of Islam, it is unlawful. That is the reason they think we are lawbreakers and we must be rebuffed. For that reason we feel compromised,"

he said.

He has recently been kept by the Taliban - and fears his work has jeopardized his family as well.

"They took me to the police headquarters approaching about whether I'd worked for an unfamiliar government. Fortunately they tracked down no proof in my home or on my telephone.

"Be that as it may, I don't believe it's the end. They are watching out for me."

From Kabul and then some, an extended time of Taliban rule

Who are the Taliban?

Ammar is one of in excess of 100 educators who worked with the British Council, in broad daylight confronting position, who have been abandoned in Afghanistan. Large numbers of them are ladies.

Nooria was likewise essential for an English-instructing program.

"It was trying as far as we were concerned. Certain individuals had fanatic considerations, and would frequently get out whatever you are instructing is inadmissible to us. Wherever we went, we were viewed as delegates of the British government.

"Some considered us spies for the UK." That, she says, endangers her and her family in Afghanistan under Taliban rule.

family at risk in Afghanistan under Taliban rule.

While the group announced a general amnesty for everyone who worked for the previous regime and its allies, there is mounting evidence of reprisal killings. The UN has documented 160 cases.

Nooria has been in hiding since the Taliban seized power in August last year.

"It's really stressful. It's worse than a prisoner's life. We cannot walk about freely. We try to change our appearance when we go outside. It's affected me mentally. Sometimes I feel like it's the end of the world," she said.

She accuses the British Council of discriminating between its staff.

"They relocated those who worked in the office, but left us behind. They didn't even tell us about the Afghan Relocation Assistance Policy (ARAP) when it came out."

Nooria and the other teachers have now applied for relocation through another UK scheme called Afghan Citizens Resettlement Scheme (ACRS), but have so far only received reference numbers.

The British Council says that when the ARAP scheme first opened, the UK government only considered applications from employees which included their office staff but not the teachers and other contractors.

They also say they have been pushing for progress with the UK government.

The UK Foreign Office has said that British Council contractors are eligible for relocation under the ACRS scheme, and that it's trying to process applications quickly but there's no answer on how long that could take.

"It's only if a contractor dies that I think they might take prompt action. And then they might feel that, yes, they are at risk. Now let's do something. I think sooner or later, this is going to happen," Ammar said.

Some of the teachers are from the Hazara ethnic minority, who have been persecuted by the Taliban, and have repeatedly been attacked by Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP), the regional affiliate of the Islamic State group. There have been three explosions in Hazara-dominated areas of Kabul in just the past 10 days.

But the path to safety is even more uncertain for those who worked with the UK government in some other roles.

Jaffer worked as a senior adviser facilitating the implementation of UK government-backed development projects in Afghanistan.

He was directly employed by British companies - some founded by the UK government, others given contracts by it. He also worked in similar roles for the US government, including at bases of the US military.

Even prior to 2021, Jaffer had received threats from the Taliban, during a wave of killings carried out by the group that targeted prominent Afghan civil society members.

He showed us one of the notes he received, which accused him of being a spy for foreign governments and threatened that he would be killed for his "betrayal of the Islamic faith".

Since August last year, Jaffer has moved location seven times.

He showed us a summons letter sent to his family home earlier this year, from the Taliban's interior ministry asking him to go to a police station for investigation. He's received three such letters.

"I've been in hospital because of stress and shock. I can't sleep. The doctor has given me strong medicines but even those don't help much. My wife is also suffering from depression. I don't let my children go to school. I fear they might be recognised," he said.

Jaffer has been refused a special immigrant visa (SIV) from the US, because he's unable to get a recommendation letter from his supervisor who died due to Covid-19.

During the chaotic evacuation which followed the Taliban's unexpectedly quick takeover of Afghanistan, Jaffer had been called to the airport by a UK official. Along with his young children and his wife, he sat in a bus outside the airport for six hours.

"My son was feeling sick, but we couldn't even open the windows of the bus, because people outside, desperate to get out would try to enter. The Taliban were firing in the air. My son saw that and he was so traumatised."

It was the same day the airport was attacked by suicide bombers who killed more than 180 people.

The UK on-the-ground evacuation process was wrapped up, and Jaffer and his family didn't get through.

Since then, he's only received a case number from the UK government in response to his application to the ARAP scheme.

"I worked with them. I facilitated them. Our Afghans on the ground didn't hate them [foreign nationals] because we convinced people to allow the projects to take place. We faced the threats, and now I'm left like this. I don't have any place in the world where I can live with safety and dignity," he said, his voice quivering as he spoke.

"What will my children's future be? My daughter can't study. I had big dreams for her. Will my young sons become extremists? I keep asking why did I bring them into this world. If this is what their future is going to be maybe they shouldn't be alive," he said.

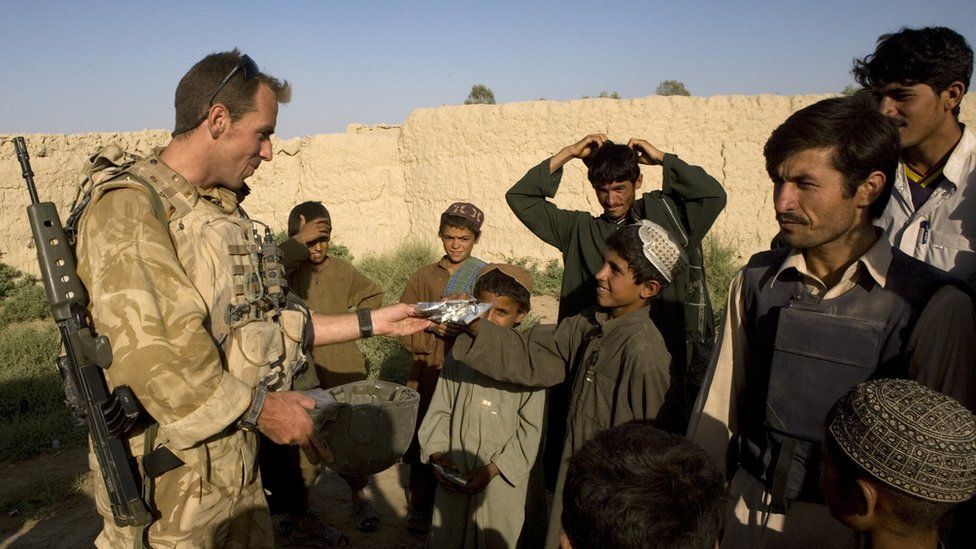

We spoke to at least three other people who worked with the UK government, including a combat interpreter who went to the front line with British troops. They all spoke of a sense of betrayal by people they risked their lives for.

The UK government evacuated 15,000 people in August last year, and 5,000 more people since then.

But thousands more are waiting, living each day in fear, stuck in limbo, expectantly looking at their email inboxes for a thread of hope.

"I used to be proud of working for the UK government," Nooria said.

"But I regret it now. I wish I'd never worked for them because they don't value our life and our work, and have been cruel in leaving us behind."

- Names in this piece have been changed to protect the identity of the contributors

0 Comments